LES VISITEURS DU SOIR (1942)

Fiche Technique – Synopsis – Revue de Presse – Story (english) – Comments (english) – Affiches – Photographies rares de la collection Michel Giniès – Liens – La Bande-Annonce (Dailymotion)

FICHE TECHNIQUE

Scénario et dialogues : Jacques Prévert et Pierre Laroche.

Découpage technique : Marcel Carné.

Images : Roger Hubert, assisté de Marc Fossard et Maurice Pecqueux.

Assistants réalisateurs : Pierre Sabas, Bruno Tireux et Michelangelo Antonioni.

Décors et costumes : Georges Wakhévitch, d’après les maquettes d’Alexandre Trauner.

Musique : Maurice Thiriet.

« Joseph Kosma a participé, dans la clandestinité, aux chansons des Visiteurs du Soir. Malgré divers arbitrages depuis 1945, le dissentiment opposant MM.Thiriet et Kosma sur les détails de leur collaboration ne nous permet pas aujourd’hui de créditer le travail de ce dernier avec certitude. »

source : SNC/M6.

Enregistrement : orchestre de la Société des concerts du Conservatoire, dirigé par Charles Munch.

Chanson interprétée par Jacques Jansen.

Son : Jacques Lebreton.

Montage : Henri Rust.

Interprètes : Arletty (Dominique), Marie Déa (Anne), Jules Berry (le Diable), Fernand Ledoux (le baron Hughes), Alain Cuny (Gilles), Marcel Herrand (Renaud), Roger Blin (le montreur de monstres), Jean d’Yd (l’homme à l’ours), Gabriel Gabrio (le bourreau), Pierre Labry (le gros seigneur), Pieral (l’un des trois nains), François Chaumette (un page), Simone Signoret (une figurante du banquet des fiançailles), Alain Resnais (un figurant), Georges Sellier (un figurant), Jean Carmet, Michelle Audrey (Agnès).

Production : Scalera/Discina (André Paulvé).

Tournage : Studios Saint-Maurice et La Victorine (Nice) ; Vence, Gourdon, Tourrette-sur-Loup ; d’avril à septembre 1942.

Sortie : 5 décembre 1942 au Madeleine-Cinéma (Paris).

Durée : 120 minutes.

Distinction : Grand Prix du Cinéma français 1943.

Prix Cinémonde et Film du meilleur réalisateur français (1944).

Note : L’exclusivité parisienne au Cinéma Madeleine dure plus d’un an.

SYNOPSIS

En ce joli mois de mai 1485, le baron Hugues célèbre en son château les fiançailles de sa fille Anne avec le Chevalier Renaud. Soudain, arrivent deux ménestrels dont l’art est de chanter l’amour et ses jeux cruels et tendres. Mais si Gilles et Dominique chantent si bien l’amour, c’est pour mieux le tourner en dérision. Fidèles serviteurs du Diable, leur sort sur la terre est de troubler les amours des humains. Et c’est pourquoi Gilles réussit à séduire Anne cependant que Dominique gagne les hommages du chevalier Renaud et du baron Hugues.

REVUE DE PRESSE

JEUX ET POESIE, fin 1943 (André Bazin)

Les Visiteurs du soir ont surgi dans la morne production 1941-1942 comme un événement révolutionnaire. On a tout de suite compris qu’il marquerait une date, le début d’une influence, l’origine d’un style. Le photographe a su créer ici des images parfaitement en accord avec le drame, sèches, blanches et noires, dépouillées et lumineuses comme le paysage méridional qui en constitue le fond. Ce poème en langue d’Oc n’a pas besoin de l’équivoque de l’ombre pour élaborer ses maléfices. Le mystère est tout entier dans l’âme des êtres et des choses qui offrent sans détour leur apparence brûlée de soleil.

LE PETIT PARISIEN, 12/12/1942 (François Vinneuil)

Voici aujourd’hui le dernier film tourné par Marcel Carné depuis l’armistice, les Visiteurs du soir. Il comble tous nos voeux. En compagnie de son fidèle scénariste, Jacques Prévert, Marcel Carné s’est si bien échappé de ses drames bourbeux que nous le retrouvons au beau milieu du pays des légendes, dans ces temps du Moyen Age où le merveilleux était si familier aux hommes. On ne peut assez louer la délicatesse et la sûreté avec lesquelles Carné a su marier le symbole, l’allusion, le goût prodigieux qu’il y a dans la composition de ses moindres images, ces jeux d’éclairage si raffinés qui forment, d’un bout à l’autre du film, l’accompagnement le plus expressif au poème d’un grand amour…

LE JOURNAL, 1943 (Émile Henriot)

…c’est là que je voulais d’abord en venir pour applaudir à leur exploit, qui est de ramener le cinéma à la poésie, c’est-à-dire à l’invention, à l’imagination, aux grandes libertés de l’esprit…

L’OEUVRE, 9/12/1942 (Jean Laffray)

Le film de Marcel Carné marque une date dans l’histoire du cinéma français.

AUJOURD’HUI, 12/12/1942 (Hélène Garcin)

Marcel Carné vient, avec les Visiteurs du soir, de réhabiliter à la fois le cinématographe et le cinéma français. L’atmosphère extra-terrestre dans laquelle baigne ce poème cinématographique s’impose dès les premières séquences. … Arletty est, dans cet ensemble étonnant, d’une indicible beauté. Marcel Carné seul sait utiliser cette comédienne dans un registre qui correspond à ses dons les moins galvaudés et les meilleurs. La voilà — et nous avec elle! — vengée de l’Amant de Bornéo et autre Boléro.

LE CRI DU PEUPLE, 16/12/1942 (Georges Champeaux)

Il faut louer MM. Jacques Prévert et Pierre Laroche d’avoir conçu cette belle légende, si délicate et si riche de symboles. Peut-être faut-il louer davantage encore M. Marcel Carné de l’intelligence avec laquelle il l’a traduite. Rompant résolument avec la fantasmagorie traditionnelle, il a créé le climat fantastique par la seule vertu de la poésie.

STORY (english)

In Jean Queval. Marcel Carne. New index series n°2 – BFI. November 1950.

May, 1485. The Baron Hugues gives a banquet in honour of his daughter Anne and her fiancé, thé Chevalier Renaud, himself one of the Baron’s warlords. Enter a troop of buffoons, among them Gilles and Dominique, who can sing and dance, soberly and delightfully. But they are a dangerous couple, with a magical power and fascination. Gilles seduces Anne, while both the Chevalier and the Baron fall in love with Dominique who, like Gilles, is intent only on bringing about disorder and heartache. Both of them have been sent by their master, the Devil. At one point, however, the latter’s plans go wrong. Gilles is genuinely in love with Anne. The Devil is obliged to arrive at the castle in perron. He causes Gilles to be chained up in prison, and makes the Baron and the Chevalier fight a duel for Dominique. There remains Anne ; she does not believe in the Devil, her faith is in Gilles. She is chained up with him. Renaud kills Hugues. The Devil frees Gilles but deprives him of his memory. He also frees Anne, satisfied that her lover will not remember her when they meet by the fountain where they exchanged their vows. But, through the power of love, Gilles recovers his memory. The Devil changes them both into statues, the hearts of which continue to beat.

COMMENTS (english)

In Jean Queval. Marcel Carne. New index series n°2 – BFI. November 1950.

This ambitious affair arrives oddly in the course of Carné’s career, although in theme and pictorial emphasis it can be related to it without searching for gratuitous affinities. One must remember first of all that France was occupied, and a school of thought had developed in Vichy circles according to which Proust, Gide, Cocteau, Mauriac and others, together with Quai des Brumes and Le Jour se Lève, were responsible for the national » defeat. » Carné, with his marked preference for present-day subjects, could think of no satisfactory contemporary story under such hostile circumstances. Whether he would have thought of making Les Visiteurs du Soir in different times is doubtful.

On the other hand, the fact that he chose this particular escapist theme, can be explained in several ways. One of the reasons, it must be confessed, is puerile. The last scene, in which the statue’s heart continues to beat, was clear enough in its dramatic context. But that both scriptwriters had wanted the audience to understand that it had also a symbolic, patriotic interpretation had never occurred to this critic. A few years later this subtlety was explained to him by Pierre Laroche. It has also been said that the Devil was not altogether unlike Hitler. Whether anyone realised this is debatable. As for Carné himself, he used the opportunity to indulge in a film of highly plastic nature—in some ways, almost anti-cinematic. Hence the overwhelming importance of sets of a formal character, in sharp contrast to Trauner’s sets, designed with a purely dramatic intention : presumably Wakkevitch had the upper hand.

Carné seems, almost, to have worked on the debatable principle of animating huge painted scenes and frescoes, as if inspired by the old masters’ works, which themselves seems rather to call for life and liberation from the frame. In the first half, this animation is achieved by holding shots for a very long time, by very slow camera movement matched equally by slow acting and, in the opening scenes at least, a marked preference for having many figures in the came shot. Although there is no actual deep focus, the impact felt is similar. Picturesqueness and hieraticism are mingled in this slow, poetic, quite fascinating but apparently interminable overture. The sequence in the dining-hall of the brand-new white castle—the poet’s song, the dwarfs, the bear, the banquet, the dance interrupted when Gilles and Dominique immobilise the couples—entirely succeeded in creating a world and climate of its own. After that, unfortunately, the script failed to hold one’s attention, the cinematic prowess began to look theatrical, the impact was lost. It is only after this long, poetic, symbolic first part that, with the Devil’s arrival, the drama at last takes shape and the narrative gains some pace by virtue of a greater number of shots and less concentration of several characters at once. Possibly it is too late.

Stylistically, the film is a fine achievement in many directions. It might be defined as a symphony in white. The shooting script, more remarkable in minuteness of detail here than in any other of Carné’s works, leaves little to the editor. The framing is elaborate and effective, the backgrounds extensive but simple. Close-ups are rarely used, and for that reason always telling ; the photography employs subtle gradations of tone, avoiding violent or striking contrasts. Whatever tricks there are —the resurrection of the bear, the interruption of life at the banquet, and so on— remain smooth and unobtrusive. The décor, the compositions and the camerawork all contrive to convey the impression that space is no hindrance whatsoever. There is a distinctively sober quality in the costumes, designed from the famous illuminated manuscripts, Les très riches heures du Duc de Berry. The music is alternatively decorative and medieval (the songs, the dance, the table music), and symphonic (the hunt), in which the themes have breadth and eloquence.

The only notable aesthetic failure of the film, perhaps, is the uneasiness one feels in watching exteriors that are sometimes real and sometimes faked. Otherwise, the numerous incidental beauties do much to compensate for the film’s lack of narrative and emotional power. Since, however, this was a first attempt by Carné and Prévert at portraying victorious, perennial love, one may wonder if such a grand, fascinating, ornamental piece of film is more, considering its ambitious theme, than a highly distinguished failure. Les Visiteurs du Soir never succeeds in touching the heart.

Arletty brought a static poise and nobility to the part of Dominique ; Alain Cuny had obviously put his heart into his rôle, and his intonation and foreign demeanour struck a note of telling strangeness ; Jules Berry’s theatrical appearance as an ingratiating, determined devil, is hard to forget. Of the others, Marie Déa was the least convincing. The film owed much to its consistent and balanced acting, and one felt this time the director’s firm singleness of purpose in handling his characters.

» This is exactly the opposite of former films by Carné. The Provence sun has replaced the Northern mist and the poisoned air of popular suburbs. Youth and love, in which all the images are bathed, finally triumph over the Devil, whereas the Devil had the last word when Jean Gabin led the game. » (René Barjavel.)

In 1942, a competition was arranged in the Vichy zone of France about the film. Roger-Marc Thérond, later a reviewer for l’Ecran Français, won the prize. In his article he remarked : » Some people have said that cinematic rhythm is lacking in Les Visiteurs du Soir. On the contrary, it is voluntarily slow, like a swan on a lake. »

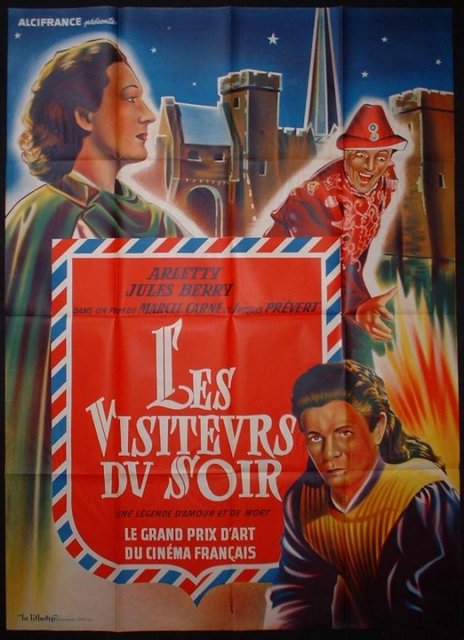

Affiches

L’affiche française lors d’une ressortie dans les années soixantes (120x160cm)

– Collection Nicolas Ruet –

Photographies rares de la collection Michel Giniès

L’équipe des Visiteurs du soir.

Marcel Carné à gauche, Jacques Prévert au centre avec le chapeau, puis Alain Cuny et Marie Déa.

Alain Cuny et Marie Déa

L’un des nains des Visiteurs du soir

Les photographies proviennent de la collection personnelle du photographe et collectionneur Michel Giniès.

Avec son aimable autorisation.

Rappelons que le photographe de plateau était Aldo.

Tous droits réservés (c)

LIENS

1 – Un très bon article sur le blog Chroniques du Cinéphile Stakhanoviste.

2 – La page consacrée au film sur le site incontournable DVDTOILE.

3 – La page consacrée au film sur le site de JEAN-LOUIS BERGAMI.

4 – La page consacrée au film sur le site SF, Horror and Fantasy Film Review (english review).

5 – Un montage photographique sur la chanson « Démons et Merveilles » sur le site Daily Motion.

6 – Une critique du Blu-ray espagnol édité par A Contracorriente Films.

LA BANDE-ANNONCE (Dailymotion)

et

Montage parallèle entre le générique en noir et blanc (1942) et le livre-accessoire qui a servi au générique (qui est en couleur).

-l’audio de ce montage provient de la bande-annonce du film-

(c) SNC/M6

Merci du compliment. à bientôt.

Je vous félicite de faire connaitre à tout ceux qui n’en ont pas la moindre idée, des œuvres qui ne doivent pas êtres oubliées. Merci